The following is a transcription of a conversation with Greg Mark, CEO and cofounder of Backflip. Most know Greg as the founder and CEO of Markforged, a continuous carbon fiber 3D printer manufacturer. He is now heading Backflip, which makes 3D shapes from prompts or sketches. Greg left Markforged in 2021 after selling it for $2.1 billion.

Roopinder: Hello, Greg! It’s been a long time.

Greg: It has.

Roopinder: Where are you these days?

Greg: It’s complicated. I split my time between New Hampshire, where I live, and San Francisco. I’ve been busy, though. We’ve got three printing rooms here now. We’re just moving out of this office, setting up a new shop. It’s been quite a journey. But let’s dive in. Where do you want me to start?

Roopinder: Start at the beginning, after you left Markforged. What came next?

Greg: After I left Markforged, I took a step back. I retired and moved to New Hampshire. It’s like the adult Disney World—the happiest place on Earth. I’m an aerospace guy at heart and always have been. I’ve flown planes, piloted helicopters and collected cars. I even indulged in some hobbies I’d always wanted to try. But after a while, I realized I missed building things. I missed creating.

I started talking to people in the industry again. I’d chat with friends, buy startups and explore what was out there. That’s when it hit me—I still had more to contribute. I wanted to build something again. At Markforged, we tackled the back half of manufacturing: taking a CAD model and turning it into something tangible, whether it was carbon fiber, titanium, or steel. But what about the beginning of the design process? That’s where I saw the potential for something new.

Roopinder: What inspired you to focus on the design side?

Greg: I spent a lot of time studying productivity—specifically, human productivity throughout the industrial revolution and beyond. The tools we use to design and create have a profound impact on what we can achieve. For example, the manufacturing processes we have today—casting, sheet metal bending, welding—were already around in the 1960s. What changed? Design. The way we approach design has transformed and that’s where innovation lies.

I’ve always wanted to live in the future, to see it come to life. To get there, we need to drive productivity per human. That’s what brings spaceships, advanced technologies and breakthroughs into reality. But the gap in productivity often stems from the difficulty in turning an idea into a design. Many brilliant craftspeople—woodworkers, metalworkers, artisans—can visualize their creations in their minds but lack the tools or knowledge to translate them into CAD models. That’s the problem I wanted to solve.

Roopinder: And that’s where Backflip comes in?

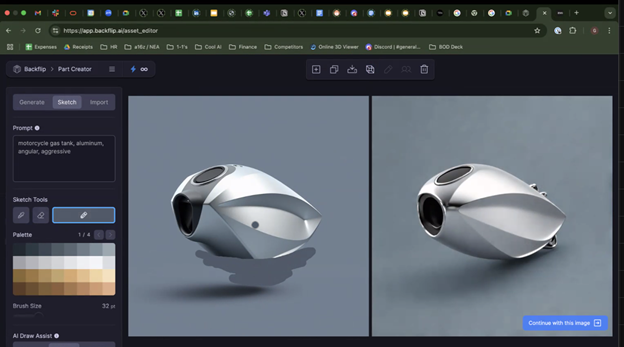

Greg: Exactly. Backflip’s mission is to bridge the gap between imagination and creation. We’re leveraging AI to help people turn their ideas into 3D models effortlessly. Imagine being able to type, “I need an angular, aggressive aluminum motorcycle gas tank,” and getting options within minutes. You can refine those options, make edits and even turn them into printable or machinable models.

Roopinder: How does it work, exactly?

Greg: It starts with a prompt. You can describe what you want in text, upload a sketch, or even provide a photograph. The AI generates multiple options based on your input. If you’re not happy with the initial results, you can refine them. Once you have a design you like, you can convert it into a 3D mesh. From there, it’s ready for 3D printing, CNC machining, or whatever fabrication process you need.

Backflip makes pretty good guesses at the shape you envision. You can modify the shapes Backflip comes up with. Here, the brush strokes below the tank are like prompts, telling Backflip to cut off a sharp edge at the bottom of the tank to make it more rounded.

We also provide tools for fine-tuning the models. For instance, if you’re working on a gas tank and want to carve away sections or modify its shape, you can do that interactively. It’s all about giving people control while keeping the process intuitive and fast.

Roopinder: That sounds revolutionary. How has the response been so far?

Greg: It’s been incredible. We launched just a week ago and over 20,000 people signed up. The demand has been overwhelming—we’ve got a backlog of users waiting to get in. It’s clear there’s a real need for this kind of tool.

Roopinder: What formats does Backflip support?

Greg: Right now, we support OBJ and GLB formats, among others. You can export entire scenes or individual parts. We also support importing various formats so users can bring in their own assets. Whether it’s character models, structural components, or props, you can integrate them seamlessly into your designs.

Roopinder: Do you see Backflip as a standalone tool or as a complement to existing CAD software?

Greg: We view Backflip as a front-end to CAD. It’s not meant to replace traditional CAD software but to make it more accessible. Many small businesses and individual users can’t afford to spend thousands of hours learning advanced surfacing techniques. Backflip empowers them to create complex designs without that steep learning curve.

For example, if you’re in Orange County Choppers and want to design a custom gas tank, you can iterate quickly with Backflip. Once you’re happy with the design, you can export it to SolidWorks or another CAD package for further refinement. It’s about turbocharging the design process.

Roopinder: Have you shown Backflip to industry leaders? What’s the feedback been like?

Greg: Yes, we’ve demoed it to some key players, including Onshape. The feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. People see the potential for Backflip to complement their existing workflows and make design more accessible to everyone.

Roopinder: Do you see a future where AI could become a geometry kernel for CAD programs like Parasolid is to SolidWorks?

Greg: Absolutely. I think AI will become an intrinsic part of the CAD process and experience. It could exist as a standalone product or integrate as a plugin within CAD software. What’s exciting is that we’re exploring uncharted territory. No one’s built something like this before, so we’re learning alongside the users about what they truly need.

One of our lighthouse customers, who hasn’t been announced yet, is very excited about an integration.

Greg: How do you feel about what CAD companies are doing these days?

Roopinder: Honestly, I’m frustrated. They’ve been stagnant for a long time and they’re not embracing innovation, especially in AI. When I talk to them, they dismiss AI as impractical. They say large language models aren’t relevant to engineering and paint AI with the same brush. But they’re wrong. Engineers don’t want to be stuck making brackets. They want AI to assist in meaningful ways, like generating designs based on context.

Greg: Are any CAD companies stepping up?

Roopinder: Not really. I see startups like Backflip are leading the charge. Some smaller companies are exploring similar ideas, but the big players haven’t made significant moves yet. One startup I saw recently, Identic AI, converts photographs of furniture into 3D models. They’re still small—only about eight people—but their work is intriguing.

Greg: I’m a huge fan of AI in mechanical engineering. It’s frustrating to see its potential go untapped.

Roopinder: Same here. Engineers need AI to be an assistant, not a designer. Generative design has been overhyped—it’s just topology optimization with a lot of marketing. Most generative designs result in impractical shapes that can’t be manufactured efficiently. I’ve challenged CAD companies to create better tools, but they’re stuck in their ways.

Greg: At Markforged, we avoided the generative design hype. It’s more of a marketing tool for 3D printing than a practical solution for engineers. Engineers know what works. We don’t need AI to reinvent the wheel; we need it to streamline the design process.

Roopinder: Exactly. Tubes, I-beams, they work. AI should help engineers create using them, not replace them with blobby shapes. I’ve issued challenges to CAD companies, like redesigning a bicycle frame. None have accepted. Instead, they make wild shapes that are impractical and inefficient. A good AI design assistant would understand the context of a project, learn from past designs and make intelligent suggestions. For example, if I’ve designed hundreds of brackets, the AI should recognize patterns and offer relevant versions.

Greg: That’s the future we’re building toward. Engineers don’t want to waste time sketching basic shapes or creating repetitive designs. AI should handle those tasks so we can focus on innovation.

Greg: Generative design often seems more like art than engineering. It’s marketed as the future, but it’s rarely practical. Engineers prioritize functionality and manufacturability. The real challenge is integrating AI into workflows without disrupting established processes.

Backflip focuses on leveraging existing manufacturing knowledge. We’re not here to disrupt the toolchain but to enhance it. The factories of the future will use the same principles and tools, but with better designs and faster iterations.

Roopinder: Have you looked at what nTop is doing? They can create organic shapes for applications like heat exchangers. CAD can’t handle that level of complexity. If AI could collaborate with tools like his, it would open new possibilities.

Greg: We’re going to work within the constraints of manufacturing while enabling innovation. For instance, car interiors might have complex, organic shapes on the outside, but on the inside, the structural components will still rely on tried-and-true methods like injection molding or stamping. The goal is to combine AI’s creativity with engineering practicality.

Roopinder: Sounds like making generative AI for shapes fit within traditional manufacturing. It reminds me of Jensen Huang of NVIDIA at CES when he talked about designing humanoid robots that can work in traditional settings. Instead of robots in a cell on a line, humanoid robots roam around the floor. This way, Backflip shapes would integrate into existing engineering workflows, enhancing what we already do well.

Greg: Exactly. AI is a tool for progress, not a replacement for expertise. At Backflip, we’re empowering engineers to bring their ideas to life more efficiently, while respecting the realities of manufacturing. The future of design lies in collaboration between human ingenuity and AI capabilities.

Roopinder: The goal is to make CAD less of a barrier to creativity and more of a tool for inspiration, right?

Greg: Exactly. CAD, when mastered, feels like a superpower—you can create amazing things. But the challenge is getting people into that ecosystem. If we can inspire more people to use CAD and 3D tools, we’ll unlock solutions to some of humanity’s biggest challenges. Think about carbon capture, Mars colonization and electric vehicles. These aren’t software problems; they’re hardware problems. We need to make hardware creation accessible to more people and fully utilize the talents of those already working in the field.

For most of human history, we’ve worked with materials directly—carving wood, shaping metal. CAD requires us to start with a blank screen, which isn’t natural for many people. At Markforged, we focused on making tools user-friendly and we’re carrying that ethos into Backflip.

Roopinder: I often rush into the shop to make something without a CAD drawings. Even for those familiar with CAD, CAD is limiting. I’m an amateur woodworker. The shapes we admire, like organic forms in furniture or nature, are hard to recreate in traditional CAD programs.

Greg: That’s where AI can shine. A year from now, the tools we have now will seem basic compared to what’s coming. AI will enable you to design those organic shapes, test variations and visualize them in 3D before building. You’ll be able to create without being constrained by the traditional limitations of CAD.

Roopinder: How did you train Backflip’s AI to design?

Greg: We built the world’s largest synthetic dataset of 3D models. Right now, it’s trained with 20 million models. By the end of the year, we’ll reach 250 million. Creating this dataset was like a Manhattan Project for CAD. Unlike text or images, CAD doesn’t have a global repository like the web. We had to generate our own data to teach the AI how to think in 3D.

Roopinder: Are you using photogrammetry to expand your dataset?

Greg: We’ve developed our own tools and are very data-private. While tools like photogrammetry are useful, they often lack precision. For instance, a photograph might require background removal or scaling. We’re building features to handle these issues intuitively, so users can quickly generate accurate 3D models from photos or scans.

Roopinder: Are you drawing inspiration from other industries, like Nvidia’s work on AI for robotics?

Greg: Absolutely. Robotics faces similar challenges in data scarcity and complexity. At Markforged, we spent a decade debugging and printing every shape imaginable. That experience taught us how to build robust 3D shape generators. We’re applying those lessons to Backflip, creating tools that understand manufacturing constraints while enabling creativity.

Roopinder: Do you think we’ll eventually see a world without traditional CAD?

Greg: Maybe 100 years from now. For now, CAD serves several critical functions, like assembling parts and creating technical drawings. AI will integrate with CAD, making it faster and more intuitive, but the core principles will remain. The future is collaborative—between humans, AI and existing tools.

Roopinder: What’s next for Backflip?

Greg: We’re doubling down on technology development. You’ll see a series of releases this year, including new tools and features. Backflip itself will evolve and we’ll also launch complementary products. Think of it like AI models—each iteration will be more powerful and user-friendly.

Roopinder: It’s been great talking to you, Greg. This is an exciting time for design and engineering.

Greg: Likewise, Roopinder. It’s been a pleasure. Let’s catch up again soon and continue exploring how to bring the future of design into the present.