Muan may be the worst place in South Korea for an airport. The south of South Korea , with its many islands, is a haven for seabirds. It has the highest incidence of bird strikes in South Korea. So, it was perhaps no big surprise to the pilot of Jeju Air flight 2216, a veteran with over 6800 flight hours, to be warned of bird strikes at 8:57 AM local time on a sunny Sunday, December 29, 2024 by Muan International’s air traffic control.

Fair warning, indeed. With the air thick with birds, one or more may have been ingested by one of the engines on the Boeing 737-800. The pilot issued a mayday alert. A local news video captured flames briefly erupting from an engine. The pilot attempts to land, but the landing gear is not descending, and he is forced to go around and try again. A few minutes later, still without landing gear down, the pilot does a belly landing. The speed is visually estimated to be “about 200 miles per hour,” higher than the 120 to 150 mph normal for a 737-800. The aircraft makes contact with the ground less than halfway down the 2,800 m (9,186 ft) runway, giving it precious little distance to slow down. A 737-800 requires a minimum of 1,830 m to stop with landing gear and brakes. Coming in hot, sliding on its belly with no brakes, no thrust reversers and with flaps level, the aircraft overshoots the runway, covers 140 meters of open ground and slams into an earth and concrete structure. It explodes in a ball of flame. Of the 175 passengers and 6 crew, only two flight attendants buckled into their jump seats at the back of the aircraft and survived, though both were seriously injured.

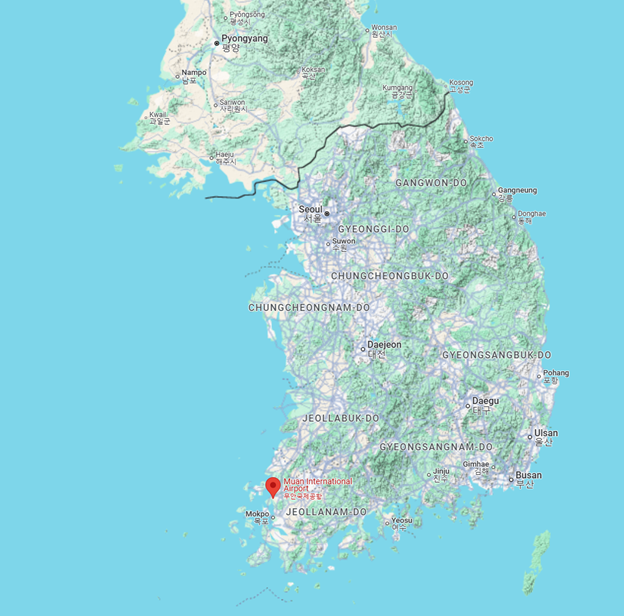

Muan International Airport is a regional airport 170 miles south of Incheon International airport in Seoul, South Korea.

The investigation has begun. We won’t know what caused the landing gear not to be deployed and if and how the landing gear failure and the bird strike were related. It will be months before an official report is available.

However, to David Learmont, a former RAF pilot and aviation journalist interviewed by Sky News, the cause is clear. He puts the blame completely on the berm, a concrete/earthen structure off the end of the runway, calling its placement “criminal.”

The berm holds the localizer for the ILS (instrument landing system), part of the aircraft sensing system that airports use, but instead of being so massive, it should have been in a more forgiving structure, says Learmont.

The pilot had been heroic, says Learmont. He executed a perfect landing under the most demanding of situations. He reviews Google Maps and visually estimates enough “level ground” after the runway to have slowed the aircraft a great deal, if not stopped it altogether, and “more people would have survived.”

The localizer, vital for bad weather and low visibility landings, are typically installed at ground level or on a “collapsible” structure, says Learmont.

From the aerial view, it may appear that the berm serves as protection for the traffic on the road encircling the airport and the highway further down, but its true purpose is to elevate the localizer.