I’ve lived in California for over 25 years. I balance the daily dread of impending disaster, be it earthquake, mudslides, flood or fire, with the beauty, the climate and, very importantly for a tech journalist, being at the center of technology. Although I am in the San Francisco Bay Area, the recent deadly wildfires in Southern California, 500 miles away, still gave me pause — and left me wondering how technology, for which the state is famous, could help detect wildfires.

Surely, I couldn’t be the first person to expect AI to help nip wildfires in the bud. Sure enough, a team at the University of California San Diego had been at this for years. They took it upon themselves to create a wireless network that uses high-definition cameras to monitor quite a bit of the state of California for fires in their early stages when they can be easily contained and extinguished. The result: ALERTCalifornia.

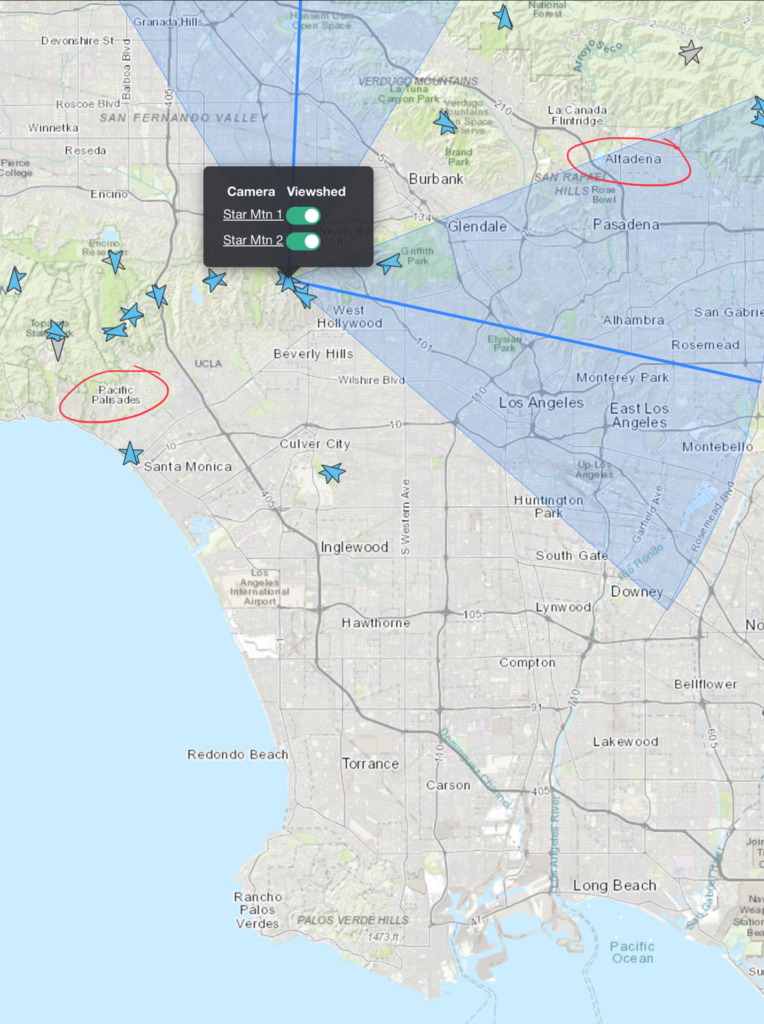

I admit my first act upon hearing about ALERTCalifornia was shamefully selfish: I checked if my house was covered. It was. Two cameras were on top of Mt Burdell, a mile from my home, and were scanning my neighborhood. Remembering the poor, wretched people of Southern California, I pull myself out of my well-protected neighborhood to see what coverage was afforded those in the Los Angeles area, those hardest hit by the recent wildfires. They were. There were, in fact, a ring of cameras around the city of Los Angeles.

My excitement at finding out that AI had been on the job quickly gave way to a question: Why with quick AI-assisted wildfire detection did the wildfires get out of control and burn down entire neighborhoods? Was ALERTCalifornia able to alert the fire departments in time? If not, why not?

ALERTCalifornia, California’s Best Kept Secret.

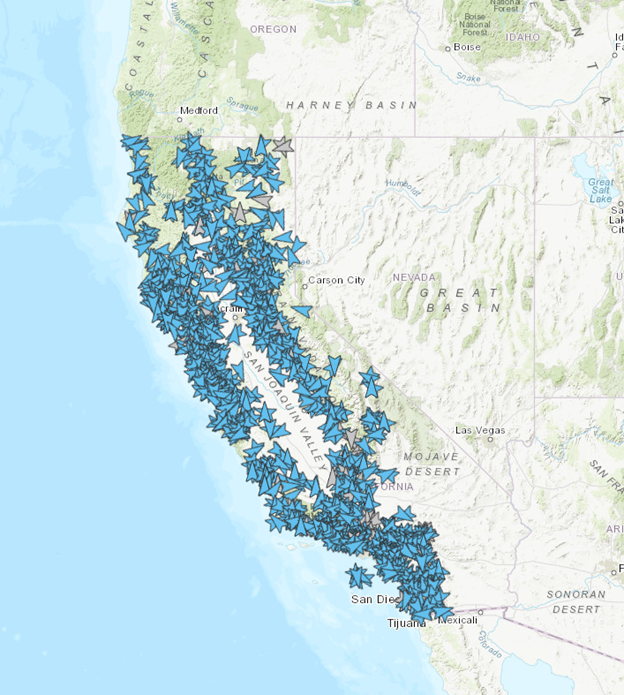

Why had I not heard of a wildfire detection system as big as ALERTCalifornia? Over 1100 camera systems, including two that were visible from my favorite hiking path. Could this be California’s best-kept secret or is it just me that needs to get out more? A quick survey of friends and family convinced me of the former. Everyone I asked about ALERTCalifornia thought it was a good idea but none had heard of it.

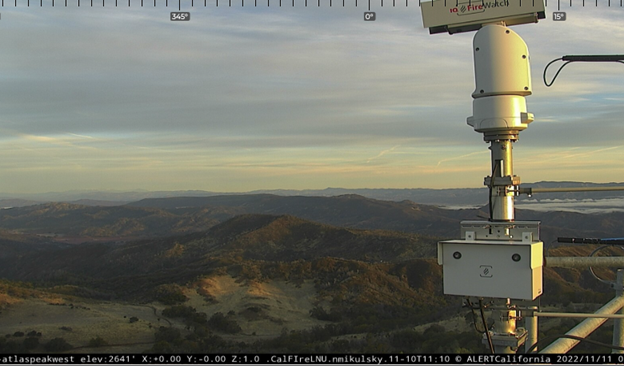

The ALERTCalifornia network relies on over 1100 cameras, many of them with a 360-degree view, most mounted on towers, many on hilltops. The high-definition cameras are able to pan, tilt and zoom. Camera control is limited to first responders; however, the public is limited to routine sweeps or, in the case of a fire, a human operator has locked into a fire, seeing what they see.

The high-definition cameras do a 360-degree sweep approximately every two minutes, capturing 12 high-definition frames per sweep. They also provide 24-hour monitoring with up to 60 miles on clear days and with near-infrared night vision, 120 miles on clear nights.

An enclosure below the camera houses the transmitting hardware that wirelessly connects to fire monitoring hubs operated by CAL FIRE fire, plus a power supply and backup batteries.

ALERTCalifornia seems to make use of existing towers wherever possible, taking advantage of electric power supply but in remote areas, they construct their towers and use solar panels for power.

Hills of Fire

Forty-five of the over 1100 ALERTCalifornia live feeds were offline at the time of this writing, including Mt. Diablo, the tallest point in the East Bay area of the San Francisco Bay Area. There is no information made public on the cause, but running out of power is certainly a possibility.

The Hughes Fire burned over 10,000 acres across Los Angeles and Ventura counties, while fires in Riverside County tragically took three lives and destroyed dozens of homes. In Altadena, a fast-moving fire consumed several hillside acres, threatening neighborhoods before firefighters managed to contain its spread. It was the Palisades Fire that got most of the attention as it scorched a heavily wooded area in one of the more affluent areas of Los Angeles neighborhoods, home for celebrities and millionaires.

Compilation of the Palisades Fire, the single most destructive fire in terms of property damage in California. CREDIT: ALERTCalifornia | UC San Diego

Human in the Loop

ALERTCalifornia is intended to augment California’s full-time fire spotters, not replace them. I imagine it to be a welcome technology, saving fire spotters from the dreary task of watching absolutely nothing for over 99% of the time. In addition, the human fire spotter is limited by fog and darkness. The AI system doesn’t get bored, and with FLIR, forward-looking infra-red, able to see through fog and darkness.

Upon detection of what might be a fire, ALERTCalifornia’s AI scans camera images looking for “anomalies,” explains Sean Landavazo, Intel Battalion Chief at Cal Fire.

“When we go in and look at the anomalies, it [the AI] gives us a 55% chance that it smoke—not fog, dust, shadows,” says Landavazo in a video shot about a year ago, “and we are training it to get better.”

The Competition

Private companies, such as Pano AI, also offer AI-assisted wildfire detection. Pano’s system is very similar to ALERTCalifornia in that it also integrates ultra-high-definition cameras, satellite data and sensors to deliver real-time wildfire detection. Pano systems have been deployed in California, other western states, Texas, and other states and countries, including Australia and Canada.

Pano AI’s customers include government agencies, power utilities, private forest owners, and ski resorts. It charges $50,000 per year as an all-in fee, covering its camera stations as well as software, maintenance, notifications, and services.

The company says its systems now monitor nearly 20 million acres around the world and have spotted almost 100,000 fires.

Other startups, including Dryad and Robotics Cats, are also using sensors, satellites, cameras, and AI to improve wildfire detection.

Little Fires, Big Wins

ALERTCalifornia makes a big deal out of putting out small wildfires. That is exactly how it should work. It is intended to be the canary in the coal mine, so to speak. When it works, it is an almost insignificant fire — but a bit AI story.

ALERTCalifornia scored an early success in detecting a fire in Grass Valley at 5:19 am on September 11, 2023. The first 911 call reporting the fire did not come in until 40 minutes later. By then, firefighters were already on the scene.

In the first two months of its implementation, ALERTCalifornia issued 77 alerts of wildfires before 911 calls were made, according to Time magazine.

ALERTCalifornia alerted the Orange County Fire Agency of an “anomaly’ which turned out to be a vegetation fire in the Black Star Canyon area at 2 am on December 4, 2024. The fire department swooped down on the fire and limited the burn to less than a quarter-acre.

Blind Spots

But as extensive as the coverage of ALERTCalifornia may seem, it may not be enough. California is a big state and 1,100 cameras provide a fishnet rather than blanket coverage. My house, for example, is not in the line of sight of any of the close-by cameras as a hill obscures it. ALERTCalifornia desperately needs more cameras yet does not allow Californians to volunteer their cameras, according to the FAQs on the ALERTCalifornia site.

It’s possible that ALERTCalifornia cameras spotted the fire and the message did not get to firefighters. Or so many alerts were issued that harried fire departments could not keep up. Fire crews could have undermanned or run into other snags, like no water supply, that prevented them from containing the fires. Or did the Santa Ana winds, blowing at gale force make fire spread inevitable?

We can only hope that the official investigations that are sure to follow will shed some light on the failures, whether they be the AI, infrastructure, manpower or bureaucratic missteps. Or will corrections and blame be of little use in a state that must come to terms with inevitable firestorms, with every rainy winter growing vegetation that turns into fuel in dry, hot summers?