It was a shot heard—and seen—around the world. Lauren Tomasi, a reporter from Nine News Australia, was reporting from the scene of the LA protests against forced deportations. She flinched when she heard a shot go off behind her. Then one officer turned toward her and fired his weapon. She fell to the ground. It was a “rubber bullet.” According to her employer, she was bruised but otherwise unharmed.

Not so lucky was a British freelance photographer, who was also hit in the leg by a similar, if not identical, bullet. The “3-inch plastic bullet” penetrated his leg. A medic applied a tourniquet to stop the bleeding, and he required emergency surgery.

The same day New York Post photographer Toby Canham was hit on the forehead from about 100 yards away, again with a similar bullet. He got it on film. Canham suffered a blood bruise and whiplash.

Another journalist, @cerisecasle.bsky.social, posted an image on X of a round fired at her and protesters, though it is unclear where she was struck.

There will likely be more injuries as the protests continue, since the number of police, National Guard, U.S. Marines and protesters is growing.

A Little History

Non-lethal rounds have been in police use, here and abroad, for about 60 years. They first burst upon the scene during the Vietnam War protests in the U.S. and used bean bags and wood. Rubber bullets were used in Northern Ireland in the 1970s by British soldiers but since they were just a thin rubber over metal rounds, they can hardly be considered non-lethal. Still, they gave us a name that persists to this day — and a false idea that being rubber, they are, for the most part, harmless. One might conjure up an image of a rubber band snapping, harmlessly bouncing off without breaking skin or bone.

Nothing could be further from the truth, say human rights groups and responsible news organizations. In the New York Times article “Rubber Bullets and Bean Bag Rounds Can Cause Devastating Injuries,” published after protests against police brutality in May of 2020 in San Jose, California, one case stood out. There was Breanna Contreras, a 21-year-old college student, who was hit in the right eye. A fellow protester who came to her aid was shot in the groin and had to be hospitalized. Eleven people were hospitalized that day. In the same article, but in a protest in Austin, Texas, medics described treating an 18-year-old who was hit in the head with a beanbag round and fragments of his skull were sticking out of his wound.

Rubber bullet rounds are still used in several parts of the world, including India, Israel, Myanmar and Turkey.

The most prolonged and devastating uses of dangerous ammo billed as non-lethal have been in the Kashmir region of India, which is contested by Pakistan. The Indian army uses rubber bullets and shotgun pellets to quell protests and often aims high. Blindness resulting from eye injury is all too common.

After hundreds of documented deaths, the term “non-lethal” gave way to the more accurate term “less-lethal.”

How Do They Work?

To reduce serious injury, some police forces are trained to aim low or even to ricochet rubber bullets off the ground, a practice known as “skipping,” presumably to reduce velocity on impact. In the U.S., most police departments have switched to large-caliber rounds with non-metallic blunt tips, which in theory spread the force over a larger area, causing bruising but not breaking skin or bone.

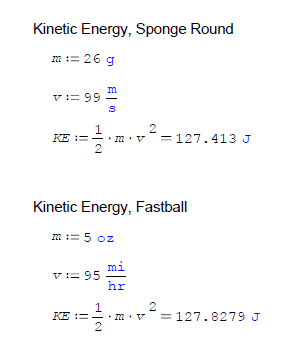

Still, the kinetic energy is significant. Getting hit by a “rubber bullet” may not be as lethal as getting shot with an AR15–style rifle, but it can feel like being hit by a Major League fastball or an ice hockey puck from a slap shot—two of the most dangerous projectiles in sports. In both sports, batters and goalies wear protective helmets and masks to prevent serious injury.

Who can forget Tony Conigliaro of the Boston Red Sox? He was hit below the left eye by a fastball thrown by Jack Hamilton of the California Angels, breaking his cheekbone, damaging his retina, and dislocating his jaw. The shock wave from the impact shattered molars.

Kinetic Energy of Dangerous Projectiles.

Ice Hockey Puck — NHL Slap Shot

Mass: 6 oz (0.17 kg)

Velocity: 100 mph (44.7 m/s)

Kinetic Energy: ≈ 170 joules

MLB Fastball

Mass: 5 oz (0.14 kg)

Velocity: 95 mph (43 m/s)

Kinetic Energy: ≈ 128 joules

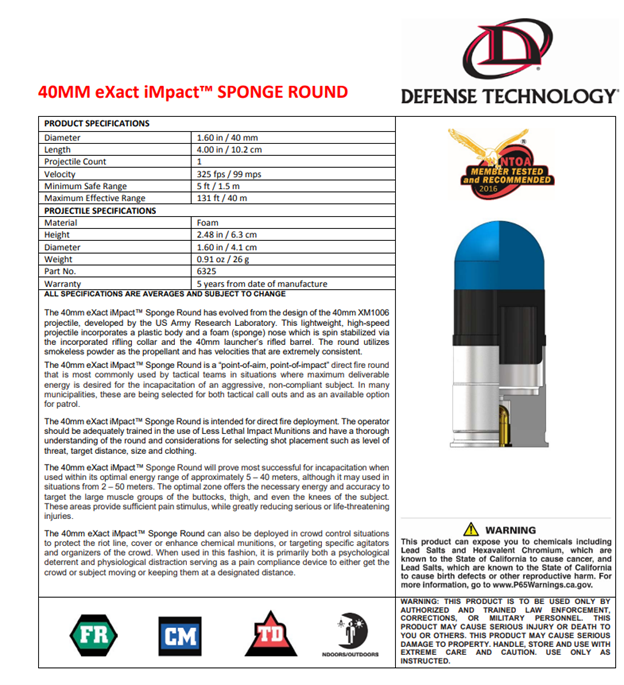

40 mm Sponge Baton Round (likely used by LAPD)

Mass: 0.026 kg

Velocity: 99 m/s

Kinetic Energy: ≈ 127 joules

LAPD Use of Less-Lethal Rounds is Illegal — Except When it Isn’t

The LAPD is the largest user of 40 mm less-lethal weapons, according to the Los Angeles Times, which also reports that officers receive training on their use and tactics and operate as part of a team. Some officers may carry shields, while others fire weapons. They are instructed to aim for the “navel area,” hands, or legs, and to avoid the head, neck, spine, groin, and kidneys, but videos and reports from the protests suggest otherwise.

Perhaps the seminal study of less-lethal weapons is My Eye Exploded, a 48-page report documenting the abuse of kinetic energy projectiles (KEPs) by police and military forces around the world, including in the U.S. The title refers to the testimony of a protester who suffered devastating injuries during the 2020 Minneapolis riots after George Floyd’s death. Dozens of people suffered eye injuries, brain trauma, and other serious harm from KIPs.

That level of brutality led states to adopt laws limiting the use of KEPs. One of these states, surprisingly enough, is California. Assembly Bill No. 48, Law Enforcement: Use of Force, Chapter 404, signed into law on September 30, 2021—states that “any law enforcement agency shall not use kinetic energy projectiles and chemical agents to disperse any assembly, protest, or demonstration.”

I read that passage several times, each time in disbelief, finding it impossible to reconcile the law with the news I had been watching and reading. How could the pervasive use of KEPs be allowed when it was so clearly forbidden by state law? There it was, right on page 1. The answer must be in the rest of the bill. I read on. I didn’t have to read much further. In the next paragraph was a loophole big enough to drive a SWAT truck through. KEPs are permitted “to defend against a threat to life or serious bodily injury to any individual, including a peace officer, or to bring an objectively dangerous and unlawful situation safely and effectively under control.”

And what could render a person under control if not being struck by a projectile with the destructive energy of a major league fastball? That would most certainly take the fight out of the enemy. Fire away, LAPD. It will take time before the courts rule on whether there was indeed a “threat to life or serious bodily injury,” or if situation was “objectively dangerous” or the protests “unlawful.”